DermArt: where medicine, art, science and technology meet

5 February 2019 | Written by Giovanna La Vecchia

We interviewed Massimo Papi, creator of the event that merges different disciplines, offering a new way to look at science

The evolution of Neuroscience has allowed us to understand how our brain processes the images we observe, opening up new opportunities that range from art to medicine. And precisely these two areas, art and medicine, seemingly so distant from each other, meet at DermArt, a “transversal” convention of dermatology born from the intuition of the doctor, painter and writer Massimo Papi, now at its tenth edition. The international event, held in the most evocative places of historic Rome, brings together doctors, nurses, biologists, cosmetologists, psychologists, art lovers and critics, and experts in technology and science from all over the world.

Thus, DermArt brings together seemingly distant universes which, by integrating, give life to new interpretative and observational modalities and to original didactic and formative possibilities.

Waiting for Dermart 2019 “The mask of the skin: colored canvas”, scheduled for September 20th and 21st in Rome, we met Massimo Papi, creator and director of the event, member of the scientific committee of Hi-tech Dermatology and of International Journal of lower extremity wounds and peer rewiever of various international specialized journals (Archives of Dermatology, Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology).

How and why was DermArt born?

DermArt is born from the pleasure of observing art and from pictorial practice that requires attention to colors, details and the composition of an image. From this consideration derives the personal pleasure of interpreting the cutaneous manifestations according to the basic elements that compose them: colors, lines and shapes. It is an operation that we all unconsciously do when we carefully observe an image, a scene, a person, any event, situation, object, in any field. The visual elements (colors, distribution lines and shapes) are incorporated in our “visual brain” and, in relation to our knowledge and experience, allow us to understand what happened before an instrumental diagnosis.

What has been the evolution of DermArt over the years in relation to technology?

The evolution of DermArt has been determined by the progressive discovery of the Neurosciences and in particular of the Neuroestetica that studies the relationship between the observation of artistic images and the functioning of the brain as a receptor and image processor.

The new acquisitions in this field have created a series of elements that can also be transferred to the observational activity of doctors and dermatologists in particular.

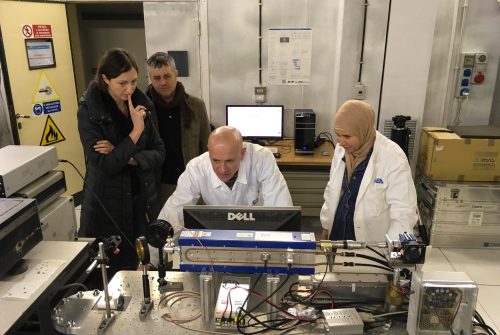

The possibility of recording, with computerized systems, the movements of the eyes when we observe a surface (in this case the skin), has induced the development of the eye tracking technique that can also be used in dermatology to understand how we look and what we see.

Technology and art. How do these components blend?

The senses still have a primary role in clinical dermatology, even in those diseases that need to be diagnosed with technologically advanced methods to be defined.

In 2012 the “Con_tatto” project was born with the objective, shared by the creators Alessio Gismondi (wood designer / faber – Company Code-a-barre) and myself, to transfer the dermatological diseases from the exclusive medical sector to the field of art with the aim of helping people to reflect gently on the topic of skin diseases. To this end, Alessio Gismondi has designed and produced a mobile-type, in a limited series of nine copies. The design of the furniture is inspired by the human body, with legs that detach the body of the container from the ground. Each anthropomorphic complement is made unique by a different decorative finish: leather. The skin of each element has been personalized with reference to specific dermatological pathologies whose characteristic signs have been used as a decorative element. In addition to the colors and shapes, the tactile elements were reproduced, just to invite the public to a physical “contact” with “diseases”.

For its high scientific and artistic value and for the real social function attributed to the objects made, “con-tatto” has been selected and included in the inauguration of the MUSE (new Museum of Science of Trento by Renzo Piano).

Earlier you mentioned the eye tracking, tell us about this technique.

Regarding eye tracking, this is an experiment presented in DermArt 2018 (see website) with which young and not so young dermatologists and non-professionals, have been called to look at the computer images of skin diseases and art. The movement of their eyes on the images subjected to observation, was recorded through specific sensors. The result will be published for the new developments and in consideration of the interest aroused. Eye tracking is a technique that can record the dilatation and contraction of the pupils, creating an effective eye tracking that defines the entire path made by the eye during the vision. It is born for clinical purposes, with the aim of understanding how the mechanisms of human vision work, identifying what you are looking at any time or with what level of attention. When you look at something, in fact, the eyes move at least 3 or 4 times per second, following an apparently random order. Each movement, called saccade, lasts about a tenth of a second, while the stops, or fixations, last from 2 to 4 tenths of a second.

Recent studies show that there is a significant correlation between dilation (mydriasis) and interest or attention to a certain stimulus, and between contraction (miosis) and aversion or disarray.

Attention, in general, focuses on a small portion of the perceived information, but represents a necessity for the progress of the process. The understanding of information at the local (semantic) and global level (in relation to the context, so as to remain sedimented in memory and to influence an attitude towards choice), together with unconscious emotional processes, has a direct influence on individual actions.

There are numerous tools that can be used to measure the attention during the execution of a task, such as an electroencephalogram (EEG) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), capable of identifying the most active areas of the brain when a person makes decisions. An instrument that deserves to be mentioned here, if only for the simplest use with respect to the aforementioned, is the Eye Tracking Device. This technique consists in recording the dilatation and the contraction of the pupils, creating an ocular trace able to define the entire path effected by the eye during the vision”.

An instrument also used in other areas?

Of course, widely used in marketing and advertising studies, for example to formulate hypotheses about the successes and weaknesses of a marketing campaign, before it is presented to the public, simply by observing the eye movements of a potential customer between the shelves of a shop. And not only. Thanks to Eye Tracking it is possible to deduce the level of attention of a person towards one or more objects, the way of treating information, as well as the exploration strategies, of a page.

How can this tool be a valuable ally? In other words, what can pupillometry tell us about how to acquire information and evaluate the managers of a large organization?

A recent study by Kramer and Mass (October 2016) provides interesting results in this regard. The intent was to analyze the eye movements of some managers while studying the information contained in the subordinate scorecards, which contained the reference values and the current scores related to different performance measures, looking for attention biases that in some what extent could they explain the evaluation bias.

The results suggest, for example, that the scorecard configuration is able to shift the attention of the evaluator to some items rather than others and that the evaluators tend to give greater importance to the tables placed at the top of the screen. Instead, it seems that attention decreases progressively by going downwards. Moreover, it would seem that managers are not immune to the so-called “primacy effect”, so that more attention is given to the information presented above than the others.

Medicine changes, necessarily, adapting more and more to the new needs of both the doctor and the patient, what is the value of DermArt in this sense?

Currently, our discipline is no longer just “clinical” but has been enriched with technically evolved diagnostic tools but sometimes a bit “cold” in judging an expression that can have different meanings, but not less rich in colors and lines.

However, if we think for example epiluminescence, an innovative technique in clinical dermatological diagnostics, most of the visual reliefs from which we obtain diagnostic judgments, is based on visual aspects of colors, lines and shapes present in the lesion in question.

Dermatological diagnostics have made great strides but observational aspects are also essential for most of these methods.

Therefore, training to grasp visual elements and details from the frontal observation, allows knowing how to interpret new and advanced technological images with greater precision and amplitude.

What is the reaction of professionals and patients to these new methods?

For doctors who are passionate about art, DermArt’s initiatives have become a fixed appointment in which to rediscover new clinical stimuli and the pleasure of discussing an original cognitive and didactic model. Biologists, psychologists and doctors of other disciplines are increasingly numerous and actively participate with the spirit of fundamental transversality for any innovative form of knowledge. The great participation of people who are not experts in art or medicine is the real success of these meetings, a testimony that the mixture of art and science can create an unexpected and fruitful source of reflection and knowledge.